The identification of pupils with Autism or on the Autistic Spectrum at a level where an EHCP (Education and HealthCare plan) is necessary would appear to account for a significant proportion of the unplanned and unfunded growth in spending on SEND, according to the latest DfE data on Special Needs. Special educational needs in England: January 2022 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

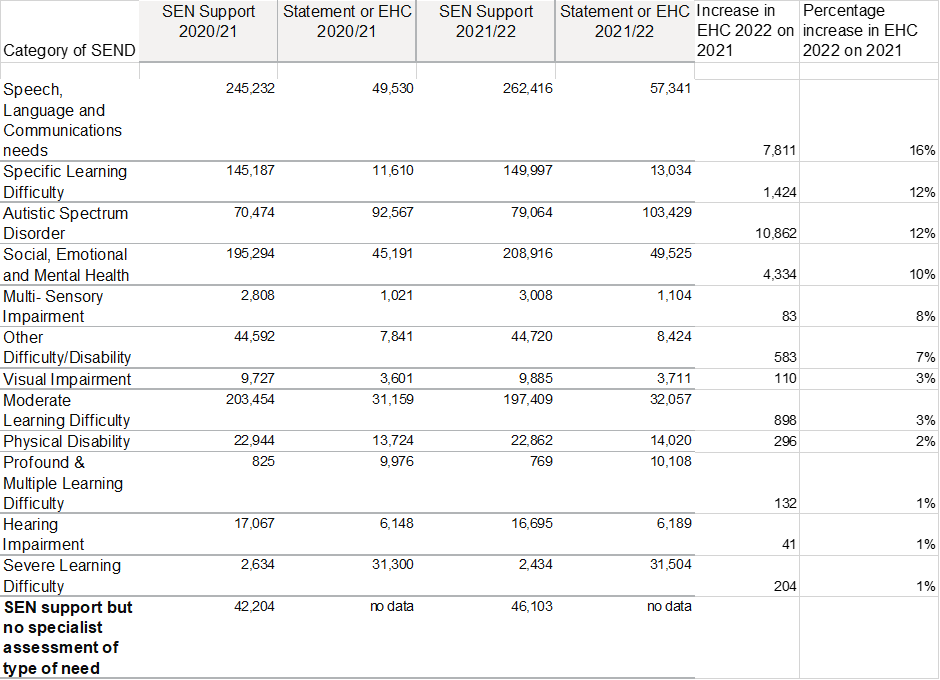

The number of EHCPs for young people on the Autistic Spectrum increased from 92,567 in January 2021 to 103,429 in the January 2022 census of pupils. To put this into some context, there are only around 10,000 EHCPs for young people with either a visual or hearing need leading to a requirement for an EHCP. Even, in the category of Social, Emotional and Mental Health, the number of EHCPs in place only increased from 45,191 to 49,525 between 2021 and 2022. However, I suspect this might increase over the coming year if predictions about the mental health of young people following the pandemic come to pass.

The growth in EHCPs was even larger for young people with speech, language and communications needs than for those diagnosed as with an autistic spectrum disorder, although this group still only account for half as many EHCPs are for young people on the autistic spectrum disorder group.

Growth in support at this level must mean a radical rethink about how the SEND sector operate. There is no way that this number of young people can be educated in the present Special School sector. Indeed, the staffing of that sector is an issue where a spotlight needs to be shone fairly quickly. There are too many unqualified staff ‘teaching’ these young people, and no visible tracking data for the adequacy of the professional qualifications on top of the basic QTS that such teachers hold. Staying in a mainstream school with an EHCP might be something many parents would need to balance against the journey time to a special school and the more generous staffing of such schools against the qualifications of the staff.

A nine per cent overall increase each year in EHCPs also places a financial burden on more rural local authorities where transport and often that means a driver of a taxi plus another person for each additional EHCP. With fuel costs rising almost by the day, the forward pricing of these contract for next year must already be causing headaches for local authority budget makers.

I don’t have the answers to this issue, but it must be of serious concern that there is sufficient finance for our most vulnerable children to receive as good an education as possible so that they can lead fulfilling lives as adults.